Dear Parishioners and Friends,

The second week of December seems to be the standard time of year when live performances of Handel’s Messiah take place. Such was the case when I was a student at Siena College back in the 1970’s and I sang with the Capitol Hill Choral Society in Albany. Several Siena students were part of the 75-voice community choir that performed four concerts a year; Messiah being the most popular, requiring two performances each December.

Since that time, I’ve attended only a few performances in person, but I try to listen to a recording each year. Streaming services have given me the choice of many different recordings by dozens of choirs and orchestras. Collegium Vocale Ghent has become one of my favorite “early music” ensembles ever since I heard them sing Bach’s Christmas Oratorio at Lincoln Center several years ago.

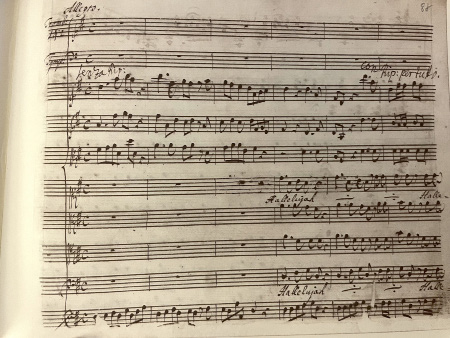

Lately I’ve become drawn to learn more about the genesis of Handel’s venerable oratorio. Earlier this year I acquired a facsimile of Handel’s conducting score of Messiah. This is different from his “autograph score” – the originial score he wrote himself. My fascimile is the score used for the first performance of the oratorio in Dublin on April 13, 1742 which was written by copyists from Handel’s original manuscript and was used for rehearsals and performances. Here is the first page of the Hallelujah chorus:

There is something uniquely special about seeing the pages that Handel himself followed as the singers and instrumentalists brought this majestic work to life, and it makes me wonder what it must have actually sounded like back then.

A brief history of the oratorio can be found in The Making of Handel’s Messiah by Andrew Gant, published by the Bodleian Library of Oxford University, which I highly recommend.

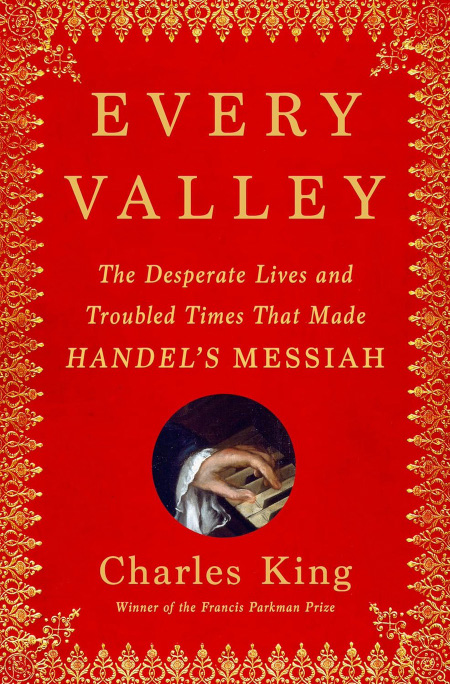

Just recently I came across a new book titled Every Valley: The Desperate Lives and Troubled Times That Made Handel’s Messiah by Charles King. Here is a brief excerpt:

“Wade into the words of the Messiah, and it isn’t hard to find a kind of message in a bottle: a reflection on some of the largest questions of human life, written at a moment—warring, worried, and somehow just wrong—when people could feel the urgency of answering them. In an age supposedly governed by progress, why do the nations so furiously rage together? Why do people concoct vain and bizarre versions of the truth? What do we do with the knowledge of our own brokenness—our listless wandering, astray like sheep—and the trail of blood that our actions, and our obliviousness, will leave in the historical record? Adrift in a maddening world, is there really a way to live the advice that Handel set to song from the book of Isaiah: ‘Lift up thy voice with strength; lift it up, be not afraid… Arise, shine, for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee’?”

The author looks at the world in which Handel was working back in the mid-1700’s and draws parallels to the world in which we are living now in 21st century. I haven’t gotten too far into the book, but I am fascinated by his approach, and I look forward to see the conclusions he draws. I anyone else up to joining me? I would love to share your reactions.

If you don’t see me this weekend it’s because I am somewhere between Strasbourg, Cologne and Brussels, taking in the sights, sounds, and tastes of those cities’ famed Christmas Markets which draw me in every five or six years. And if I could have managed to do so, I would be at Notre Dame Cathedral participating in its grand reopening following the devastating fire of April 2019.

Blessings on your week ahead!

Fr. Tim Shreenan, O.F.M.

Pastor